Today’s post comes from Janae Gallant and Megan Lamb. Janae is an honours student in Psychology at Carleton University and Megan is the Resource Coordinator of the CON-SNP National Executive. You can find more about Megan here!

HAES Promotes Obesity

Honestly, I’m not sure what this means. Claiming ‘obesity promotion’ implies a simplified – and I’ll say it – wrong – understanding of what obesity even is and how it comes to be.

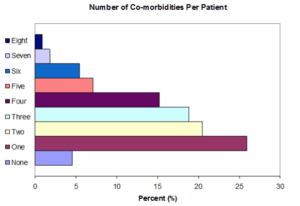

To clarify, some factors that impact obesity are: environment, genes, mental health, medical comorbidities, medications, and sleep (Buchholz et al., 2013).

Notice that feeling good about your body, which is the bottom line that HAES promotes, is not even a so-called “cause” of obesity.

Figure 1. Medical and Mental health Status of Children and Youth with severe complex obesityBuchholz, Hadjiyannakis, Rutherford, Mohipp, Clark, Adamo, & Goldfield (2013)

Simplified understandings of obesity overlook the established fact that significantly altering your body composition is incredibly difficult, and that increasing exercise and restricting caloric intake will not lead everyone to thinness.

Obesity is a complex chronic condition – this means that managing obesity is a lifelong process. While the usual recommendations for lifestyle changes often lead to short term weight loss, these changes are short-lived and have little effect on long-term weight-related health outcomes. HAES promotes a weight-neutral approach to weight-related comorbidities that has actually shown to improve physiological and mental health more sustainably than simply preaching increased exercise and restrictive diets in clinical trials (Bacon & Aphramor, 2011).

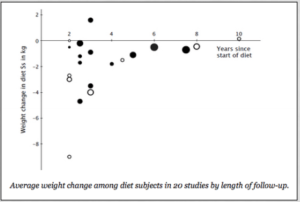

In addition, diets don’t work!

When comparing long term weight loss studies, research suggests that the longer the study, the greater the weight re-gain (Tomiya, Ahlstrom & Mann, 2012).

Tomiyama, Ahlstrom & Mann, 2012

On the other side of the debate, some HAES enthusiasts suggest that a balanced diet and exercise don’t make you “healthier”, but we recognize that this is also more complex than it seems at first glance.

While HAES should represent empowerment and self-love, that should include treating your body with respect, and rather than focusing on weight-loss, we should be focusing on improving health behaviours.

To clarify, research shows that intuitive eating, physical activity, and sufficient sleep will all benefit overall well-being (Bacon, Stern, Van Loan & Keim, 2005). More specifically, these behaviours may lead to increased energy, higher self-esteem, and potentially decrease the burden of obesity related comorbidities – with or without influencing weight itself (Bacon, Stern, Van Loan & Keim, 2005; Bacon et al., 2002).

It is time to go back to the roots of the HAES movement.

It should be about accepting different body types and understanding that “health” aligns with more than one of them. At the core of the issue we need to understand that even if we all ate the same diet and engaged in similar physical activity we would continue to look about as differently as we do now. Given its persistence, body diversity and its resistance to change might as well be embraced and celebrated.

While this is a controversial movement that has been misinterpreted by many, we can combat its misconceptions with sound research and common sense. The societal harm to having people with overweight and obesity feeling comfortable in their bodies is non-existent.

In fact, research suggests that having a positive body image is actually protective against weight gain because people are more likely to treat their bodies well when they are comfortable in them (i.e. eating a balanced diet, engaging in physical activity, sleeping more). In addition, research shows that having self-compassion can lead to better health and quality of life (Attie & Brookes-Gunn, 1989; Stice & Shaw, 2002).

Adults and children alike are exposed to a lot of garbage when it comes to how a person is expected to look and feel about their bodies. If we aren’t willing to accept body diversity within healthcare it puts people at high risk for the development of a poor body-image, which only further fuels obesity and overweight.

So, the next time you think about the HAES movement, don’t think about it as an obesity promoting movement or a movement against eating in a nutrient dense way. Think of it as a movement to make children of all shapes and sizes grow up to feeling good in their own skin – good enough that they want to fuel their bodies in a way that gives them energy; good enough that they feel comfortable participating in physical activity because they are not being constantly shamed for looking “different”; good enough that they grow up without fixating on food or exercise and are instead able to enjoy both.

Through HAES children and adults alike are given the freedom to enjoy treating their bodies well because they love themselves, not because they are trying to drastically alter their shape or weight. If the ultimate goal in providing healthcare is longevity and improved quality of life then embracing HAES is a necessary aspect of all care provision – weight-related or otherwise.

While getting fully on board with HAES can take some time and contemplation, at least consider the following:

- Obesity is complex

- Recognize your biases and attempt to break them

- Focus on health NOT weight loss

- PROMOTE BODY ACCEPTANCE

References

Attie, I., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (1989). Development of eating problems in adolescent girls: A longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 25(1), 70–79. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.25.1.70

Bacon, L., & Aphramor, L. (2011). Weight Science:Evaluating the Evidence for a Paradigm Shift. Nutrition Journal, 10(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-10-9

Bacon, L., Keim, N. L., Van Loan, M. D., Stern, J. S., Gale, B., Kazaks, A., & Stern, J. S. (2002). Evaluating a “non-diet” wellness intervention for improvement of metabolic fitness, psychological well-being and eating and activity behaviors. International Journal of Obesity, 26(6), 854–865. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0802012

Bacon, L., Stern, J. S., Van Loan, M. D., & Keim, N. L. (2005). Size acceptance and intuitive eating improve health for obese, female chronic dieters. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 105(6), 929–936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2005.03.011

Buchholz, A., Rutherford, J., Mohipp, C., Clark, L., Adamo, K. B., Goldfield, G., Hadjiyannakis, S. (2013). The medical and mental health status of children and youth with severe complex obesity. Paper presented at the 3rd Canadian Obesity Summit, Vancouver, May 1-4.

Stice, E., & Shaw, H. E. (2002). Role of body dissatisfaction in the onset and maintenance of eating pathology: A synthesis of research findings. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 53(5), 985–993. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00488-9

Tomiyama, A. J., Ahlstrom, B., & Mann, T. (2013). Long-term effects of dieting: Is weight loss related to health? (Provisional abstract). Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7(12), 861–877.