Today’s post comes from Kerri Delaney. Kerri is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Health, Kinesiology and Applied Physiology at Concordia University. She is also the current Resource Coordinator of the OC-SNP National Executive.

Bariatric surgery is an intervention that allows individuals to control caloric intake by reducing the size of the stomach and/or altering the digestive tract. Currently, bariatric surgery is the most effective treatment for obesity and its associated metabolic complications, often allowing for drastic weight loss, weight loss maintenance and improved metabolic health (1).

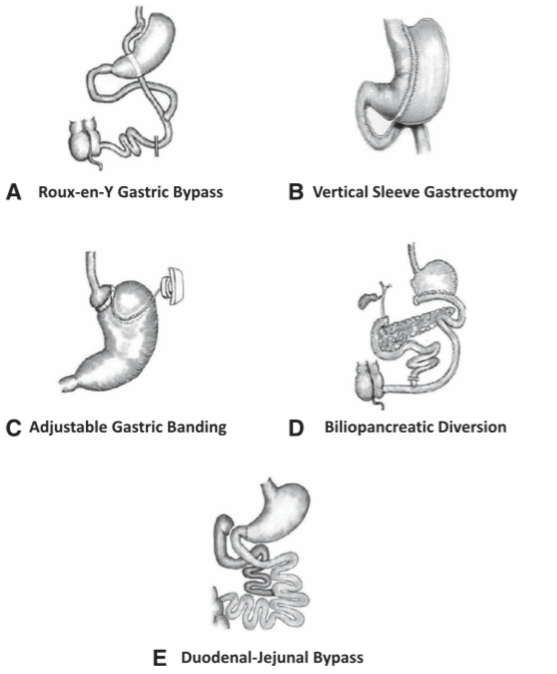

There are two categories of bariatric surgery. Restrictive surgeries, such as laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding and the gastric sleeve, reduce the size of the stomach to limit food intake (Figure 1). Malabsorptive or “bypass” surgeries, such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, biliopancreatic diversion and duodenal-Jejunal bypass, re-route the intestinal track to alter nutrient absorption (Figure 1). Malabsorptive surgeries also regularly involve an additional restrictive component. The type of surgery used is decided while weighing the overall risk of the procedure to the desired health outcomes (2).

Both categories of surgery are meant to induce drastic weight loss in patients. Compared to individuals who undergo diet and/or lifestyle interventions, individuals who have bariatric surgery often lose significantly more weight and more importantly, are able to maintain weight loss years after (3). Additionally, when compared to classical diet and/or lifestyle interventions, individuals who have undergone bariatric surgery tend to have reduced hypertension, reduced hyperlipidemia and a decreased dependence on pre-surgical medications (1). Both restrictive and malabsorptive surgeries can also influence hormonal signaling to the brain which can help reduce feelings of hunger and increase satiety (2).

In addition to weight loss, there are a number of weight independent effects of bariatric surgery. Several studies have noted the potent insulin sensitizing effect of malabsorptive surgeries in individuals with type 2 diabetes melitus (4-6). Patients often regain insulin sensitivity within days of the operation, have a reduced dependence on pre-surgical medications and long term, insulin sensitivity is often maintained (5). Recent evidence has shown that malabsorptive surgeries may additionally improve insulin sensitivity through alterations in the gut microbiome (7).

Although there are several beneficial effects of bariatric surgery, there are also a number of risks that come along with these procedures. If you are considering bariatric surgery, having detailed conversations with your health care providers can ensure that it is the right choice for you.

Image reference: Batterham, R. L. and D. E. Cummings (2016). “Mechanisms of Diabetes Improvement Following Bariatric/Metabolic Surgery.” Diabetes Care 39(6): 893-901.

Bibliography

- Sjostrom L, Lindroos AK, Peltonen M, Torgerson J, Bouchard C, Carlsson B, et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(26):2683-93.

- Rubino F, Schauer PR, Kaplan LM, Cummings DE. Metabolic surgery to treat type 2 diabetes: clinical outcomes and mechanisms of action. Annu Rev Med. 2010;61:393-411.

- Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kashyap SR. Bariatric Surgery or Intensive Medical Therapy for Diabetes after 5 Years. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(20):1997.

- Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, Guidone C, Iaconelli A, Leccesi L, et al. Bariatric surgery versus conventional medical therapy for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(17):1577-85.

- Ribaric G, Buchwald JN, McGlennon TW. Diabetes and weight in comparative studies of bariatric surgery vs conventional medical therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2014;24(3):437-55.

- Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, Guidone C, Iaconelli A, Nanni G, et al. Bariatric-metabolic surgery versus conventional medical treatment in obese patients with type 2 diabetes: 5 year follow-up of an open-label, single-centre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9997):964-73.

- Grams J, Garvey WT. Weight Loss and the Prevention and Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Using Lifestyle Therapy, Pharmacotherapy, and Bariatric Surgery: Mechanisms of Action. Curr Obes Rep. 2015;4(2):287-302.