Today’s post is brought to you by the OC-SNP Executive.

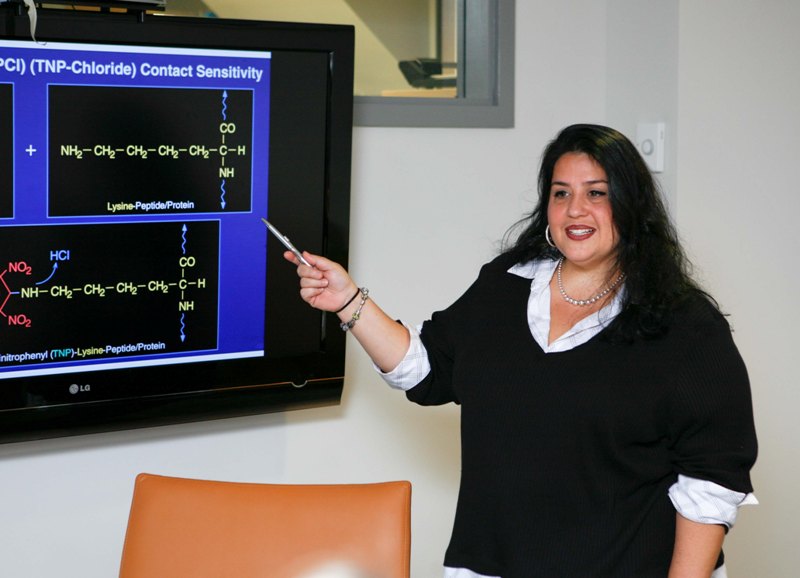

All eyes were on me as I walked up to the podium. I was about to present my obesity research at an esteemed conference, but I felt their stares boring into me for another reason. Not only was I about to deliver the most important talk of my scientific career, but I was about to speak about obesity research…in an obese body. No matter how confident I was in the talk I prepared or the research I’d performed, these thoughts flooded my mind:

Maybe they won’t take me seriously because I’m up here talking about how to prevent and treat obesity, but I’m living with obesity. They’re probably thinking, “Why doesn’t she take her own advice? If she knew what she was talking about, she wouldn’t have obesity.”

It’s been 2 years since I gave that talk and I’ve come to realize that I have to be taken seriously precisely for that reason: my lived experience informs and drives my research on and off the bench.

I’ve always struggled with obesity: ever since I can remember I was the biggest girl in the class. I remember being the biggest girl in grade 1, in grade 10, and in graduate school. I struggled with my weight in the ways that some young girls do, realizing early that my body was different than others’, but I quickly resolved that I would not allow my weight to determine what I could or couldn’t do.

Flash forward to my graduate school career, where I found myself in a lab researching the cell biology of insulin resistance caused by obesity. I’d love to say that I deliberately chose this research path, but I didn’t. When I was an undergraduate student, there was an opening in a lab that just so happened to be doing research on Type 2 Diabetes, and the rest is history. Ever since then, I’ve been researching obesity and its effects on insulin resistance. My research focuses on figuring out why the body stops responding to insulin (which is what happens in Type 2 Diabetes) in the hopes that if we can figure out why it happens, we can either stop it from happening or fix it when it does.

As part of my research, I spend a lot of time reading about obesity and diabetes on the microscopic scale: I study a lot about cells, their interactions, how they signal and communicate, and ultimately, what happens when insulin signalling fails in someone’s cells when they are diagnosed with diabetes. Because of the nature of my research, I don’t spend a lot of time researching obesity at the people level, which, I think, is a glaring problem. Almost every paper I read starts with a statistic: “this many people in this country are obese” and that’s the end of the consideration of the people living with the disease that we study. As a field (cell biology), I think we’ve failed, in part, to recognize that every initiative at the bench starts because a patient in the real world is struggling with a disease that we, on the bench, are aiming to better understand. It’s not just about cells, it’s about people. It’s not just about proteins and signalling, it’s about their experience. It’s not just about the research: the research is about the people.

I’ve stood up in quiet protest against the paradigm that only mentions people briefly at the beginning of a paper and at the end of a grant, but then ignores their lived experience. I resolved to always use people-first language, to always think about the real-world implications of my work, and to move through this field with an unwavering respect for the people living with the diseases I research and write about.

Two years later, I’ve come to realize that what I thought was my weakness is actually my strength. My lived experience with obesity makes me a better obesity researcher. It means that I’ll never dismiss a patient story; it means that I’ll handle every patient sample with the respect and care that it deserves; and it means that I’ll never forget why I’m working so hard at the bench. At first, I was disappointed and angry with the people who didn’t see our work the way I do, but now, I feel a sadness for them that they’ll never get to experience the joy of waking up everyday truly believing that you have a chance to change someone’s life one day and make their life even a little bit easier. Researching obesity while living with obesity is not an irony or a disadvantage, it’s really a superpower.

Photo credit: UConn Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity